In 1959, William Bertelsen became the unlikely star of a national science magazine.

He wasn’t a scientist. He was the country doctor of Neponset, Ill., his hometown of 500 people; he was married, with three girls and one boy. In all his days at school, he hadn’t taken a single class in aerodynamics, and only took one course in physics.

Then, at 38, his career in cooking up futuristic, unorthodox vehicles began.

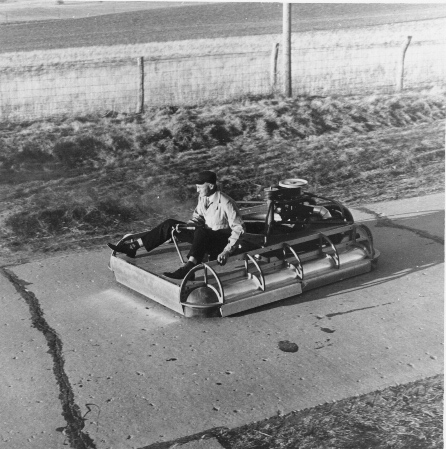

It was a mild June day when reporters from Popular Science knocked on his door, eager to photograph the newly developed “car without wheels” in his backyard. Bertelsen thought that he—and his invention—had made it big.

This June, it was Bertelsen who knocked on the magazine’s proverbial door to play catch-up. Now 88, he works part-time at a radiology clinic, and is still playing the role of amateur inventor. His life story was so fascinating that we decided to profile him again, nearly 50 years later. To put it simply, his invention (which today we’d call a hovercraft) never panned out. But it’s a bit more complicated than that.

Bertelsen’s day job was the inspiration for his craft. He dreamt it up while trying to rush to his patients’ homes—in colder seasons, a wintry mix always postponed house calls. To expedite the trip, he developed the Aeromobile 35B, an air-cushion vehicle (ACV) that glides above snow and water on a cushion of high-pressure air.

He didn’t officially invent the hovercraft—Britain’s Sir Christopher Cockerell did—but he was still a pioneer. Bertelsen was the first person to develop an ACV with a peripheral jet, which directs the high-pressure stream of air downward, rather than inward. His design provided better control than previous crafts because it could move left, right, forward and backward.

He was also one of the first people in the United States to pilot a hovercraft, which attracted attention from the government for its military potential. After the nod from Popular Science, several demonstrations for local papers, and a few tours with the International Trade Fair, Bertelsen became a small-town star. He was an example of how far an amateur scientist can go in his own garage, without academic or industrial ties pulling him along.

But his 15 minutes of fame quickly ended. By the early ’60s, Britain was already off to a head start in ACV development because the country had secretly financed one of Cockerell’s early projects in the late ’50s. America couldn’t keep up, and Britain soon became the Mecca of ACV design, rendering hovercraft pioneers in the U.S. invisible to both government officials and the general public.

Today, ACV interest throughout the world has mostly evaporated. Britain and Russia employ a few hovercrafts in their militaries, but the industry is largely confined to small pockets of hobbyists.

And while we’re on the subject, Bertelsen has never liked the term “hovercraft.”

“It’s not meant to hover, it’s meant to get places!” he says to me over the phone.

It’s a question of semantics, but his statement reflects a deep frustration with the public’s image of ACVs. Most people think of hovercrafts as elaborate toys, and not as functional vehicles. Bertelsen blames the craft’s obscurity on last century’s low fuel prices; since Americans didn’t need to find an alternative to gas-guzzling cars, they ignored hovercrafts, which could have used less fuel than automobiles. The Space Race, which redirected most military funding to outperforming the Russians, pushed ACVs further into obscurity.

But as the hovercraft declined in popularity, Bertelsen became more and more interested in the craft and all of its air-vehicle relatives. It’s the antithesis of capitalist economics—Bertelsen went where there was no market.

But just as his unreachable patients compelled him to build his first hovercraft, more noble interests continue to drive Bertelsen.

Lowering gas consumption is one of them. With an eye to fuel efficiency, Bertelsen began developing a vertical take-off and landing airplane (VTOL), a vehicle with an elliptical-shaped arc wing that attempts to solve a deficiency in modern airplanes: once you get them in the air, you want to saw off part of their wing. That’s because the lengthy apparatus, which is necessary for lift-off, slows speed and increases friction. By tipping Bertelsen’s arc wing back to garner a higher angle of attack, airplanes can leave the ground with a shorter wingspan, allowing for a much swifter ride.

In theory, at least. Bertelsen has never constructed a full-size VTOL model, let alone an actual airplane. In 2003, though, he worked with his son, W.D. Bertelsen, and the University of Illinois to apply for a NASA-funded grant that would have helped to further develop the machine.

“The committee thought our design was a little too radical,” W.D. Bertelsen says.

But Bertelsen has been closer to the edge of success. In 2000, the U.S. Coast Guard toyed with the idea of using his A-2000 vehicle, which evolved from his first hovercraft, for ice patrol and rescue. Nothing emerged. In 2007, venture capitalists expressed interest in his arc wing technology. Again, nothing.

“We’ve went as far as flying out to New York City to sign the papers for agreements to manufacture some of these vehicles,” says William Kirby, Bertelsen’s Web designer. “And they didn’t show up.”

There’s always hope for tomorrow, though. Bertelsen and Kirby say that an unnamed individual could soon invest as much as a million dollars in his gimbal-fan system, which provides a better control system for the unwieldy hovercraft. Instead of resting on an immobile surface, his engine sits on a rotational fan, a structure that can be flipped to propel the air stream horizontally or vertically. This flexibility garners lift, propulsion and restraint simultaneously.

“It’s [Bertelsen’s] most well-known, well-developed technology,” Mark Bergee, chief aerodynamicist of Geneva Aerospace, Inc, says. “It’s so well-known that the Russian scientists who developed some of the largest ground-effects vehicles thanked him because they had used it in their studies.”

Even if Bertelsen doesn’t land the investment, though, it wouldn’t all be for naught. A lifetime of dedication is nothing to frown at, and neither is an 88-year-old who’s still working, playing, and trying to revolutionize transportation.