In "Life of George Washington - The Farmer" by Junius Stearns, George Washington stands among African-American field workers harvesting grain; Mount Vernon in the background.

In his 1775 treatise, Taxation No Tyranny, British author Dr. Samuel Johnson rhetorically asked, “How is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of negroes?” The paradox that Dr. Johnson called out in 1775, is a question Americans continue to grapple with to this day—the institution slavery. The institution of slavery had been a part of American society for more than 150 years when the Revolutionary War began in 1775. Slavery existed, and was protected by law, in all 13 American colonies when they declared their independence from Great Britain in 1776.

The institution of slavery proved to be a difficult issue for the Founding Fathers to navigate. They all had been born into a slaveholding society where the morality of owning slaves was rarely questioned. While some colonies were for slavery, and others against slavery, the fact was that the institution had deep roots in the colonies. A majority of the signers of the Declaration of Independence and nearly half of the delegates to the Constitutional Convention owned slaves. Four of the first five presidents of the United States were slaveowners. As the ideals of the enlightenment began to spread through the American colonies in the 1760s and 1770s, the articulation of the ideals of liberty and freedom began to take shape. As the Revolution progressed, the issue of slavery soon became a controversial topic that eventually resulted in vast regional and political divides.

The American colonists frequently discussed slavery, but more in the context of their relationship with Great Britain. American patriots were fearful that they would become enslaved to the British. George Washington wrote to a friend his fear in 1774: “we must assert our rights, or submit to every imposition that can be heaped upon us; till custom and use, will make us as tame, and abject slaves, as the blacks we rule over with such arbitrary sway.”

The British saw an opportunity to use the slaves against their masters very early in the war. Royal Governor Lord Dunmore in Virginia did this in November of 1775, when he issued a proclamation giving freedom to all slaves who abandoned their patriot masters and joined the British side. Thousands of slaves took this offer and joined Dunmore. Many of the men were formed into a military unite called the “Ethiopian Regiment” and played a role at the Battle of Great Bridge in 1775. With thousands of slaves joining the British side, the Americans began to allow slaves to fight in the American Army, and thousands of free and enslaved African Americans ended up fighting for the patriots. It is estimated that nearly 10% of the Continental Army was African American at one point. This would be the only integrated American Army until the Korean War almost two hundred years later. Almost 5,000 African Americans fought on the side of the British.

During the war and immediately following it, Northern states began passing laws to gradually abolish slavery in their states. Pennsylvania was the first state to begin the process in 1780 and followed shortly by Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Connecticut, and Rhode Island. New York and New Jersey followed in 1799 and 1804, respectively. While these Northern states did not rely on slave labor for their agriculture, their economy was still tied to the exports from the Southern states which did rely on slave labor, especially after the invention of the cotton gin 1793.

Many of the major Founding Fathers owned numerous slaves, such as George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison. Others owned only a few slaves, such as Benjamin Franklin. And still others married into large slave-owning families, such as Alexander Hamilton. Despite this, all expressed a wish at some point to see the institution gradually abolished. Benjamin Franklin, who owned slaves early in his life, later became president of the first abolitionist society in the United States. Despite their talk and wish for gradual abolition, no national abolition legislation ever materialized.

The indispensable man of the Revolution, George Washington owned hundreds of slaves, but during the Revolutionary War, he began to change his views. He wrote that he wished “more and more to get clear” of owning slaves. Men like Marquis de Lafayette and John Laurens who adamantly opposed the institution urged Washington to work towards the abolition of slavery. Washington wrote in 1786 about slavery that “there is not a man living who wishes more sincerely than I do, to see a plan adopted for the abolition of it; but there is only one proper and effectual mode by which it can be accomplished, and that is by Legislative authority.” Washington, though, never took a public stand on the abolition of slavery. He described his ownership of slaves as “the only unavoidable subject of regret.” When Washington died, he made an important statement to the nation and freed the slaves he owned in his will, the only Founding Father to do so.

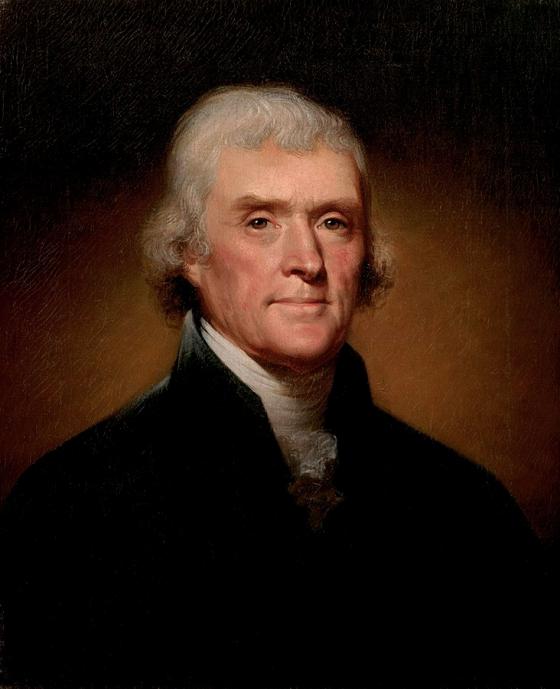

Perhaps the most scrutinized of the Founding Fathers with respect to slavery was Thomas Jefferson. The same man who wrote the very words “all men are created equal,” in the Declaration of Independence owned hundreds of slaves all his life. He also may have fathered children with one of his slaves, Sally Hemings. Despite this, he still wrote how he believed slavery to be a political and moral evil and how he wished to have the institution abolished. Jefferson felt powerless to change the situation and summed it up near the end of his life as “we have the wolf by the ear, and we can neither hold him, nor safely let him go. Justice is in one scale, and self-preservation in the other.” Despite his wish to end slavery, Jefferson never personally freed his slaves. When he died in 1826, his estate was in so much debt that his slaves were sold off to the highest bidder.

As the Founding generation passed on and as slavery continued to expand and grow in the Deep South, slaveowners began to speak of slavery less as a “necessary evil” and more as “positive good.” Events such as Nat Turner’s 1831 rebellion in Virginia soured many Southerners views of gradual abolition, as they viewed slave uprisings as a threat to their society. The institution of slavery contributed to the economic, political, and social divide between the North and South. The rise of militant abolitionism in the North provoked heated debates as to the future of the institution of slavery and who had the power to determine its future. Ultimately, these unfinished debates helped lead to the fratricidal Civil War in 1861.